Table of Contents

Adventure Game (Inheritance)

Introduction

The adventure game first appeared in Case Study 1 in Lecture 4. There we showed how Lists and Maps can be combined to produce data structures to manage the book-keeping required in a game. There, the data maintained in the collections where simple strings. in Case Study 2 we enhanced the capabilities of the system by making use of procedural code and closures. A text-based menu was introduced to support user interaction. later in Case study 3, we used objects with more interesting state information and behaviours to represent the game, the players and items. We also removed any input/output responsibilities from them and introduces another action class for this purpose.

In the first two iterations of this case study, we revisit the same case study and use class inheritance to model not just items with a name, description and values, but items in general. As with the earlier versions, we use containers to help model the relationships established between objects. Similarly we continue to make use of unit tests. In the third iteration, we address the problem of error detection and user feedback as well as enhancing the functionality of the system. Finally, in the last iteration, we demonstrate how easy it is to use Groovy to police constraints placed on the model.

An index to the source code for all the examples in this case study is available.

Specification

As in Case study 3 we assume sufficient familiarity with the operation of a text-based adventure game to understand the following description:

The game has a name, holds a number of items that may be have either weight or magical potency. weighty items and magical items both have a name, optional description, value and a unique identification number. Each weighty item has a weight and each magical item has a potency. The system should be able to display the items that can be picked up and those that are being carried. A some point in the future, the game can hold other items such as food and clothing.

There are a number of registered players, each of which has an email address, a unique identification number and a nickname. A player may pick up an item and drop an item. The system should record each transaction. To record the collection of an item, the id of the player and the id of the item are required. To record that an item has been dropped, on the item id is required.

The system should also be able to display details of the items that are being carried by players.

These requirements are captured in the use cases as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: use cases for an Adventure Game <html> <table> <tr><td> <ul> <li>Add new weighty item to game inventory</li> <li>Add new magical item to game inventory</li> <li>Display game inventory</li> <li>Display items available for collection</li> <li>Display items being carried by players</li> <li>Register a new player</li> <li>Display all players</li> <li>Player picks up a weighty item</li> <li>Player picks up a magical item</li> <li>Player drops a weighty item</li> <li>Player drops a magical item</li> </ul> </td> </tr> </table> </html>

Iteration I: Confirm the Polymorphic Effect

The specification mentions two kinds of items held in the game: weighty items and magical items. Further, we are advised that, in the future, food and clothing will also be available. This suggests a class hierarchy for the various types of game items. It should be capable of extending horizontally to include new categories of items, and vertically to further specialize the items.

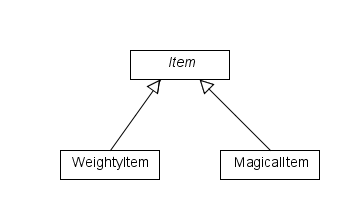

The initial class diagram is given in Figure 1. The Item class represents any item that may be present in the game. It is an abstract class and carries the properties and behaviours common to all game items: the item id, name, value and optional description as well as the toString method which provides a textual representation. The two subclasses represent the actual items currently available ion the game. in addition to the id and other properties inherited from the superclass Item, the subclass WeightyItem has a weight property while subclass MagicalItem has a potency property.

Figure 1: Initial class hierarchy

This leads us to develop the Groovy classes Item, WeightyItem, and MagicalItem held in the files Item.groovy, WeightyItem.groovy, and MagicalItem.groovy, respectively.

- 1| Item class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/Item.groovy)

abstract class Item { String toString() { // redefinition def s = "${id}: name = ${name}; value = ${value};" if ( description.size() > 0 ) { s += " description: ${description};" } return s } // ----- properties ----------------------------- def name def description = '' def id def value }

- 1| WeightyItem class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/WeightyItem.groovy)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/WeightyItem.groovy

- 1| MagicalItem class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/MagicalItem.groovy)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/MagicalItem.groovy

When deploying a class hierarchy, we need to be assured that we a correctly initializing the objects and that any polymorphic behaviour operates as expected. This is the aim of this first iteration. All all three classes refine the toString method (Item redefines toString from Object, WeightyItem and MagicalItem redefines toString from Item), we must ensure that we get the expected polymorphic behaviour.

Following the discussions of Lecture 8, we create the GroovyTestCases, WeightyItemTest and MagicalItemTest classes. In the WeightyItem class, we have:

- 1| WeightyItemTest class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/WeightyItemTest.groovy)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/WeightyItemTest.groovy

The MagicalItemTest class is similar. Notice that the unit tests also guarantee the constructor usage since the toString methods make use of the object properties.

Because we also intend unit testing other classes, we have a runAllTests to run a GroovyTestSuite, as described in Lecture 8

- 1| GroovyTestSuite class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/runAllTests.groovy)

import groovy.util.GroovyTestSuite import junit.framework.Test import junit.textui.TestRunner class AllTests { static Test suite() { def allTests = new GroovyTestSuite() allTests.addTestSuite(WeightyItemTest.class) allTests.addTestSuite(MagicalItemTest.class) return allTests } } TestRunner.run(AllTests.suite())

We can easily add other GroovyTestCases later.

An execution of the script results in the following test report:

.. Time: 0.005 OK (2 tests)

It confirms that we have the correct object initialization and polymorphic behaviour. Therefore, we have achieved the aim of this iteration.

Iteration II: Demonstrate the Required Functionality

having established that we can make use of the polymorphic effect, the aim of this iteration is to demonstrate that we can achieve the required functionality described in the use cases of the Specification.

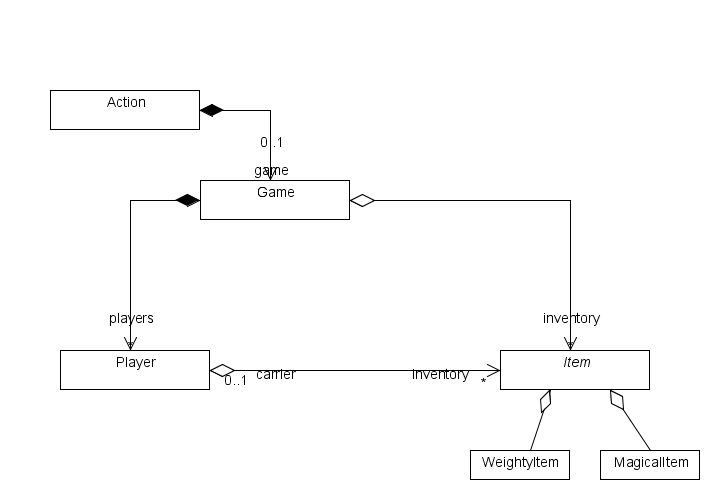

We have introduced the abstract class Item with the properties and behaviours common to all items in the game. Therefore we adjust the class diagram of Figure 3 from the previous case study to reflect this decision. It is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Class diagram

Clearly, we can base the implementation of these classes on those of Case study 3. However, we can also incorporate the changes made to Game and Player as a result of the unit testing in Lecture 8. Happily we can also retain the GameTest and PlayerTest to the GroovyTestSuite in runAllTests.groovy although we have to replace Item in the test fixtures in both GameTest and PlayerTest with WeightyItem:

// class GameTest // ... /** * Set up the fixture */ void setUp() { game = new Game(name : 'School') book = new WeightyItem(id : 1, name : 'book', value : 5, description : 'a maths text book', weight : 1) satchel = new WeightyItem (id : 2, name : 'satchel', value : 10, description : 'a carrier for school books and pencils', weight : 5) item3 = new WeightyItem (id : 2, name : 'a different satchel', value : 10, weight : 5) }

(the PlayerTest setUp method is similar).

The Action class also needs some minor changes. For example, addItem will have to be changed to addWeightyItem:

// Action class void addWeightyItem() { print('\nEnter item id: ') def itemId = Console.readInteger() print('\nEnter item name: ') def name = Console.readLine() print('\nEnter item value: ') def value = Console.readInteger() print('\nEnter item description (return for none): ') def description = Console.readLine() print('\nEnter item weight: ') def weight = Console.readInteger() def item = new WeightyItem(id : itemId, name : name, value : value, description : description, weight : weight) game.addItem(item) }

We need a similar method addMagicalItem:

// Action class void addMagicalItem() { print('\nEnter item id: ') def itemId = Console.readInteger() print('\nEnter item name: ') def name = Console.readLine() print('\nEnter item value: ') def value = Console.readInteger() print('\nEnter item description (return for none): ') def description = Console.readLine() print('\nEnter item potency: ') def poetncy = Console.readInteger() def item = new MagicalItem(id : itemId, name : name, value : value, description : description, potency : potency) game.addItem(item) }

Finally, we modify the Groovy script that presents a menu to a user and actions user choices. It is shown as Game 01.

- 1| Game 01: An adventure game with weighty and magical items (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/game1.groovy)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/game1.groovy

To complete this iteration, we run our unit tests. Happily, they all pass. Next, we use the menu to carry out functional testing. an obvious strategy is to make choices (assisted by the various display options) that correspond to the use-cases identified earlier. An illustrative session (with the user data input shown in bold italic) is: <html> <pre> e:\dev\at-m42-2009\Case-Studies\case-study-04><b><i>groovy game1.groovy</i></b>

0: Quit 1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Display inventory 4: Display available items 5: Display items being carried 6: Register new player 7: Display players 8: Pick up an item 9: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>1</i></b>

Enter item id: <b><i>111</i></b>

Enter item name: <b><i>book</i></b>

Enter item value: <b><i>5</i></b>

Enter item description (return for none): <b><i>a maths text book</i></b>

Enter item weight: <b><i>1</i></b>

0: Quit 1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Display inventory 4: Display available items 5: Display items being carried 6: Register new player 7: Display players 8: Pick up an item 9: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>2</i></b>

Enter item id: <b><i>222</i></b>

Enter item name: <b><i>potion</i></b>

Enter item value: <b><i>10</i></b>

Enter item description (return for none): <b><i>a magical potion</i></b>

Enter item potency: <b><i>5</i></b>

0: Quit 1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Display inventory 4: Display available items 5: Display items being carried 6: Register new player 7: Display players 8: Pick up an item 9: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>3</i></b>

Game: The Discworld

WeightyItem: 111: name = book; value = 5; description: a maths text book; with weight: 1 MagicalItem: 222: name = potion; value = 10; description: a magical potion; with potency: 5

0: Quit 1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Display inventory 4: Display available items 5: Display items being carried 6: Register new player 7: Display players 8: Pick up an item 9: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>0</i></b>

Game closing … thanks for playing </pre> </html>

Having encountered no problems, we consider this iteration to be complete.

Iteration III: Provide User Feedback

Following a demonstration of the previous iteration, we have been asked to provide more feedback from the system and that commonly occurring errors can be handled. The following additional use-cases are to be implemented:

- Remove an item

- Display a particular item

- Display selected items

- Display a particular player

- Display selected players

The aim of this iteration is to detect errors, give user feedback, and implement the additional use-cases.

We begin by addressing erroneous user data input. We have been advised that users may attempt to:

- Add a duplicate item

- Remove a non-existent item

- Register a duplicate player

- Remove a non-existent player

- Pick up an non-existent item

- Pick up an item that is being carried by another player

- A non-existent player attempts to pick up an item

- A non-existent item is dropped

- An item that was not being carried is dropped

- Display a non-existent item

- Display a non-existent player

Clearly, we must check these scenarios, take some appropriate action, and then inform the user. We descide that most of the checks be the responsibility of the Game class. This is reasonable because it has methods to add, pick up, remove and drop Items as well as those to register a Player.

We also decide that it is the Game's responsibility to make suitable textual messages available to the Action class for display purposes. The idea is that methods in the Game that are responsible for adding, removing, picking up and dropping items should return a String value to indicate the outcome. Methods in the Game that register a player should do the same. The resulting code for the Game class is now:

- 1|Extended Game class (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/Game.groovy)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/Game.groovy

Because we have changed the signature of the method addItem in the Game class, we have to change the existing test cases testAddItem_5 and testAddItem_6 to match the use of a return message rather than a returned boolean value. We also add some additional unit tests to test the newly added removeItem method.

/** * Test that the Game had one Item after removal of * an Item known to be in the Game */ void testRemoveItem_1() { // // book is created in the fixture game.addItem(book) def pre = game.inventory.size() game.removeItem(book.id) def post = game.inventory.size() assertTrue('one more item than expected', post == pre - 1) } /** * Test that the correct message is available to a client */ void testRemoveItem_2() { // // book is created in the fixture game.addItem(book) def actual = game.removeItem(book.id) def expected = 'Item removed' assertTrue('unexpected message', actual == expected) } /** * Test that the correct message is available to a client */ void testRemoveItem_3() { def actual = game.removeItem(book.id) def expected = 'Cannot remove: item not present' assertTrue('unexpected message', actual == expected) }

Notice that we make use of safe navigation in the removeItem method:

String removeItem(Integer itemId) { def message if ( inventory.containsKey(itemId) == true ) { ... item.carrier?.drop(item) ... } else { ... } return message }

This means that we don't have to make an explicit check that the Item to be removed is being carried. If its carrier property is null, then the message drop will not be sent and a null pointer exception will not be thrown.

A large number of other unit tests are are needed to test all the possible paths through the new Game methods. You will find them in the source code.

We also decide that the Action class should be responsible for checking the existence of a specified Item or Player before attempting to display it. It should inform the user about the nature of the problem encountered. This is a reasonable decision since it is the Action object that interacts with the user.

To implement the remaining new use-cases, we introduce two more flexible display methods. Both make use of regular expressions with Strings, as discussed in Lecture 2. The first, displaySelectedItems, displays all Items whose idd start with the String entered by the user. The second is similar and it displays all Players whose id starts with the string entered. An outline of the updated Action class is now:

import console.Console class Action { // ... def removePublication() { print('\nEnter item id: ') def itemId = Console.readInteger() def message = game.removeItem(itemId) println "\nResult: ${message}" } // ... def displayOneItem() { print('\nEnter item id: ') def itemId = Console.readInteger() def item = game.inventory[itemId] if ( item != null ) { this.printHeader('One item display') println item } else { println '\nCannot print: no such item\n' } } // ... def displaySelectedItems() { print('\nEnter start of item ids: ') def pattern = Console.readLine() pattern = '^' + pattern + '.*' def found = false this.printHeader('Selected publications display') game.inventory.each { itemId, item -> if ( itemId.toString() =~ pattern ) { found = true println " ${item}" } } if (found == false) { println '\nCannot print: No such publications\n' } } // ... def displayOnePlayer() { print('\nEnter player id: ') def playerId = Console.readInteger() def player = game.players[playerId] if ( player != null ) { this.printHeader('One player display') println player def items = player.inventory items.each { itemId, item -> println " ${item}" } } else { println '\nCannot print: no such player\n' } } // ... def displaySelectedPlayers() { print('\nEnter start of player ids: ') def pattern = Console.readLine() pattern = '^' + pattern + '.*' def found = false this.printHeader('Selected players display') game.players.each { playerId, player -> if ( playerId.toString() =~ pattern ) { found = true println player def items = player.inventory items.each { itemId, item -> println " ${item}" } } } if (found == false) { println '\nCannot print: No such borrowers\n' } } // ... private printHeader(detail) { println "\nGame: ${game.name}: ${detail}" println '===============================\n' } // ----- properties ----------------------- private game }

Note the introduction of the private printHeader method. This kind of modification during iterative development is quite common. Provides that the change is documented and tested, all should be well.

All that remains is to modify the previous Groovy script to present and action a slightly different menu to the user. a partial listing is shown in Game 02.

- 02: An adventure game with weighty and magical items with error detection and user feedback (at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-04/game2.groovy)

import console.Console def readMenuSelection() { // ... println('3: Remove an item\n') // ... println('5: Display selected items') println('6: Display one item') // ... println('11: Display selected players') println('12: Display one player\n') // ... print('\n\tEnter choice>>>> ') return Console.readInteger() } // make the Action object def action = new Action(game : new Game(name : 'The Discworld')) // make first selection def choice = readMenuSelection() while (choice != 0) { switch (choice) { case 1: // ... case 3: action.removeItem() break // ... case 5: action.displaySelectedItems() break case 6: action.displayOneItem() break // ... case 11: action.displayeSelectedPlayers() break case 12: action.displayOnePlayer() break // ... default: println "Unknown selection" } choice = readMenuSelection() } println '\n\nGame closing ... thanks for playing'

<html> <pre> 0: Quit

1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Remove an item

4: Display inventory 5: Display selected items 6: Dsiplay one item 7: Display available items 8: Display items being carried

9: Register new player 10: Display all players 11: Display selected players 12: Display one player

13: Pick up an item 14: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>2</i></b>

Enter item id: <b><i>124</i></b>

Enter item name: <b><i>potion</i></b>

Enter item value: <b><i>5</i></b>

Enter item description (return for none): <b><i>a magic potion</i></b>

Enter item potency: <b><i>5</i></b>

Result: Item added

0: Quit

1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Remove an item

4: Display inventory 5: Display selected items 6: Dsiplay one item 7: Display available items 8: Display items being carried

9: Register new player 10: Display all players 11: Display selected players 12: Display one player

13: Pick up an item 14: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>4</i></b>

Game: The Discworld:

WeightyItem: 111; name = sword; value = 10; description: a rusty sword; with weight: 10 WeightyItem: 123; name = book; value = 5; description: a book of poems; with weight: 5 MagicalItem: 124; name = potion; value = 5; description: a magic potion; with potency: 5

0: Quit

1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Remove an item

4: Display inventory 5: Display selected items 6: Dsiplay one item 7: Display available items 8: Display items being carried

9: Register new player 10: Display all players 11: Display selected players 12: Display one player

13: Pick up an item 14: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>5</i></b>

Enter start of item ids: <b><i>12</i></b>

Game: The Discworld: Selected publications display

WeightyItem: 123; name = book; value = 5; description: a book of poems; with weight: 5 MagicalItem: 124; name = potion; value = 5; description: a magic potion; with potency: 5

0: Quit

1: Add new weighty item 2: Add new magical item 3: Remove an item

4: Display inventory 5: Display selected items 6: Dsiplay one item 7: Display available items 8: Display items being carried

9: Register new player 10: Display all players 11: Display selected players 12: Display one player

13: Pick up an item 14: Drop an item

Enter choice>>>> <b><i>0</i></b>

Game closing … thanks for playing </pre> </html>

At this point we consider the iteration complete.

Iteration IV: Enforce Constraints

With graphical notations such as the UML, it is often difficult to record the finer details of a system's specifications. The aim of this iteration is to demonstrate how Groovy can help us do this.

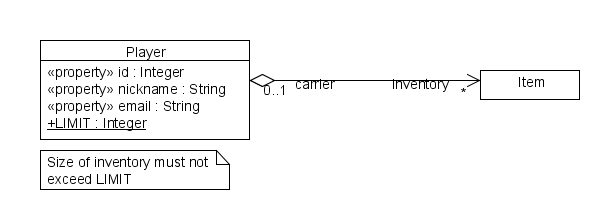

We can make assertions about our models by adding textual annotations to model elements. For example Figure 3 is a class diagram that illustrates the constraints placed on the Player class such that no player can carry more that a certain number of items.

Figure 3: A constraint shown as a textual annotation.

The text in the note describes the constraint. It may be informal English, as is the case here, or it may be stated more formally. In any event, we must ensure that the implementation that this constraint is not violated. To accomplish this, we have updated the Player class to have a public static final property LIMIT, initialized with the maximum number of Items that can be carried:

class Player { // ... // ----- properties ----------------------------- def nickname def email def id static public final LIMIT = 4 def inventory = [ : ] }

We can then make checks in the Games methods so that we don't exceed that limuit. A typical check in the pickupItem method is:

// class: Game String pickupItem(Integer itemId, Integer playerId) { def message if ( inventory.containsKey(itemId) == true ) { def item = inventory[itemId] if ( item.carrier == null ) { if ( players.containsKey(playerId) == true ) { def player = players[playerId] if (player.inventory.size() < Player.LIMIT) { player.pickUp(item) message = 'Item picked up' } else { message = 'Cannot pickup: player has reached limit' } } else { message = 'Cannot pick up: player not registered' } } else { message = 'Cannot pick up: item already being carried' } } else { message = 'Cannot pick up: item not present' } return message }

As usual, we update the Game's unit tests to confirm that the code executes as expected. For example we have:

// class: GameTest /** * Test that over limit message works */ void testPickupItemCannotExceedItemLimit() { def item4 = new WeightyItem(id : 444, name : 'item 4', value : 4, weight : 4) def item5 = new MagicalItem(id : 555, name : 'item 5', value : 5, potency : 5) def item6 = new WeightyItem(id : 666, name : 'item 6', value : 6, weight : 6) // // book, satchel and item3 are created in the fixture def itemList = [book, satchel, item3, item4, item5, item6] game.registerPlayer(player) def actual itemList.each{ item -> game.addItem(item) actual = game.pickupItem(item.id, player.id) } def expected = 'Cannot pickup: player has reached limit' assertTrue('unexpected message', actual == expected) }

Since Groovy's testing system is so easy to use, it encourages us to do more testing. For example, we can impose constraints on the relationships that exist among objects rather than on object in isolation. The relational constraints start at some object and then follow architectural links to other objects before applying some test. For example, we can assert that if we navigate from any Item being carried by a Player, then the inventory of that Player must contain a reference to an Item with which we started. In other words, any Item being carried by a Player must be consistent.

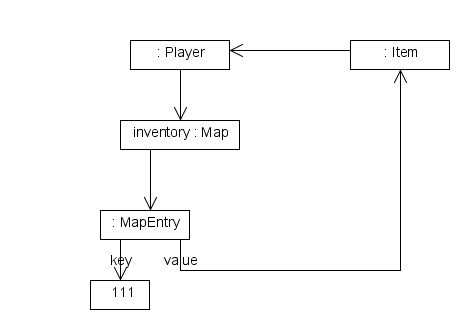

This is an example of a loop variant. although it does not concern us here, loop invariants are widely used in formal approaches to software development where proof of correctness is important. For our purposes, we just need to demonstrate that if we start at some object and follow a sequence of object links, then we arrive back at the same object. The object diagram of Figure 4 illustrates this.

Figure 4: An Item-Player loop invariant.

The figure shows that if we start from a given Item and navigate to its Player, then we should find the Item's id is a key in the Player's map of carried items. For the model to be consistent, the associated value for that key should be the Item with which we started. We code the invariant check in Groovy as:

// class: Game private void checkItemCarrierLoopInvariant(String methodName) { def items = inventory.values().asList() def carriedItems = items.findAll{ item -> item.carrier != null } def allOK = carriedItems.every { item -> item.carrier.inventory.containsKey(item.id) } if (! allOK ) { throw new Exception("${methodName}: Invariant failed") } }

Since the violation of an invariant indicates that a serious error has occurred, we terminate the system by throwing an Exception with a suitable error message. Notice that we do not declare that the method throws an Exception (see Exceptions).

As before, we only check methods that are likely to cause a violation. In this case it is just the method pickupItem.

// class: Game // ... if (player.inventory.size() < Player.LIMIT) { player.pickUp(item) this.checkItemCarrierLoopInvariant('Game.pickupItem') message = 'Item picked up' } else { message = 'Cannot pickup: player has reached limit' } // ...

Before we finish, we must create at least one unit test to check that the expected Exception is thrown. this turns out to be problematic since we have coded the pickUp method in the Player class to ensure that the loop invariant is not violated.

One solution is to create a MockPlayer subclass whose redefined pickUp method as the required abnormal behaviour:

class MockPlayer extends Player { Boolean pickUp(Item item) { if (! inventory.containsKey(item.id)) { // // Normal behviour commented out // inventory[item.id] = item item.pickedUpBy(this) return true } else { return false } } }

We create a MockPlayer object in the unit test where a Player object would normally be expected.

// class: GameTest void testCheckItemCarrierLoopInvariant() { def mockPlayer = new MockPlayer(id : 1234, nickname : 'chris', email : 'cpj@swan.ac.uk') game.registerPlayer(mockPlayer) game.addItem(book) game.addItem(satchel) try { game.pickupItem(book.id, mockPlayer.id) fail('Expected: Game.checkItemCarrierLoopInvariant: Invariant failed') } catch (Exception e) { // ignore exception } }

Note that the method fail reports a failure only if the Exception has not been thrown. The MockPlayer class is an example of the mock object testing design pattern. It avoids polluting normal code with abnormal behaviours.

Happily all the tests in the runAllTests script pass. Therefore, at this point, we conduct functional tests by executing a Groovy script from the previous iteration. As expected, no problems occur and we consider this iteration to be finished.

Home | Lectures | Previous Case Study | Case Studies | Next Case Study