if-then-else statement instead.Table of Contents

Adventure Game (Methods and Closures)

This case study is intended to be used for self study. It is designed to reinforce the materials covered in lectures and practised in the laboratories. It also forms the basis for the project work.

An index to the source code for all the examples in this case study is available.

Introduction

This case study illustrates the power of Groovy methods and closures by constructing solutions to the small case study first introduced in Lecture 4. As before, we present a simple model of the items in a text-based adventure games. Our game maintains a record of the names of the items in the game and the names of the players who are carrying one or more items.

As in Case Study 1, we develop the game application as series of iterations. This lets us add functionality to the application ins a controlled manner. It also ensures that we have a working (partial) solution as early as possible. The first iteration demonstrates that we can achieve the required functionality, while the second. In the third iteration, we simplify the coding of the second. Our aim is to make the code easier to understand and maintain.

Iteration I: Specification and Map Implementation

The problem specification requires that we manage and maintain the inventory of the game. We are required to implement the following use cases:

- Add and remove items to/from the game

- Record the picking up and dropping of an item by a player

- Display details of the current game

- Display the items being carried by a given player

- Display the number of players who are carrying a particular item

Having established an external view of the application in the use cases, there are various ways in which could model and implement a solution. We have already seen two possible solutions in Case Study 1, namely using List or Map data structures. For this iteration, we shall use a Map to represent the items in the game. One reason for this choice is that the Map is ideally suited for the efficient storage and retrieval of information. We anticipate that this will be useful for implementing the game application.

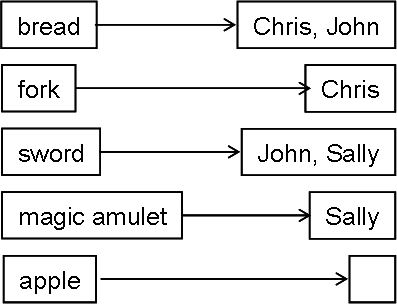

Our intention is that the Map will be keyed by the name of the item and that each corresponding value will be a list of the players who are carrying that item. We have made an assumption that there will be a copy of the item for each player named in the List. Another useful feature of the Map is that its keys are unique. This eliminates the possibility of duplicate entries for a named item in the game's database.

In the Map, the value for each key is a List whose elements are zero or more Strings. Each String represents a player's name. Note that a List can contain duplicate elements so we are making the assumption that the same player can be carrying several copies of the same item (say two gold coins) at the same time. A List can alos be empty. in this case, the item that the item name represents is not currently being carried by any players. A simple initialization of the game database is:

- 44

def game = [ 'bread' : ['Chris', 'John'], 'fork' : ['Chris'], 'sword' : ['John', 'Sally'], 'magic amulet' : ['Sally'], 'apple' : [] ]

The resulting Map data structure is illustrated diagrammatically in Figure 1. The figure shows that Chris and John are both carrying bread, Chris is carrying a fork, John and Sally are both carrying a sword, and Sally is carrying a magic amulet. Notice that the item named apple is not being carried by anyone, reflected by the fact that the value is an empty List.

Figure 1: Simple Map data structure for the game application.

Figure 1: Simple Map data structure for the game application.

The functionality required by this simple application is easily realized by Groovy methods. Each method implements one of the use cases identified from the specification. Had any of them proved particularly complicated, then, of course, we could have broken them down into simpler methods. Note that although we use the term “method”, we might just as well have used the term “procedure” in this context, because we are essentially taking a procedural approach to the development of this case study.

To access a List of player names associated with a particular item, we use the Map index operator [ ] with the item name as the index value. This simplifies the coding task considerably. For example, to add a new item to the game we have:

and to determine the number of players carrying an item, we have:

As in the partial listing of Game 01, most of the other methods are just as straightforward. For the sake of simplicity, the various output displays are initentionally kept simple, we will remedy this later.

- 4| Game 01: The methods in an Adventure Game (Full source at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game1.groovy)

def addItem(game, item) { game[item] = [] } def removeItem(game, item) { game.remove(item) } def pickUpItem(game, item, player) { game[item] << player } def dropItem(game, item, player) { game[item].remove(player) } def displayItems(game) { println "The game contains: ${game} \n" } def readNumberOfItemsBeingCarried(game, player) { // get a List of each List of the players from the game def playerNames = game.values().asList() // create a single list fo the players' names playerNames = playerNames.flatten() // return the number of palyer names in the List return playerNames.count(player) } def readNumberOfPlayersHoldingItem(game, item) { return game[item].size() }

Notice that each method has game as a formal parameter, This is in keeping with a procedural style of software development in which procedures read or write to/from a central data structure. In our case study, this data structure is of course the game database, which is implemented as a Map.

To test that our methods work as expected, we develop a test case for each use case. in this simple case study, we just check the output visually, and assume perfect input data. For example, the test case for the display of the items in the game simply prints the underlying Map to the console screen. We compare the output visually with that expected from the initialization of the Map. Clearly, this approach does work, but is not very realistic. Later, in Lecture 8, we shall discuss testing in more detail. However, for now, this approach will suffice.

As with the iterative development of the application, it is often useful to introduce test-cases incrementally, that is one at a time. This reduces the risk that the testing burden might overwhelm us and builds confidence in ouur software as testing progresses. For example we might start with the script

- 40|Game 01: The first test case (Full source at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game1.groovy)

// methods as shown previously // ... // initialize the items in a game def game = [ 'bread' : ['Chris', 'John'], 'fork' : ['Chris'], 'sword' : ['John', 'Sally'], 'magic amulet' : ['Sally'], 'apple' : [] ] // Test case: Display items in a game println 'Test case: Display items in a game' displayItems(game)

happily, it produces the expected output:

Test case: Display items in a game The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[]]

We now add another test-case:

- 53| Game 01: The second test case (Full source at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game1.groovy)

// methods, initialization and test case as shown previously // ... // Test Case: Add a new item println 'Test Case: Add a new item' addItem(game, 'knife') displayItems(game)

Again, it produces the expected output:

Test Case: Add a new item The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[], knife:[]]

We continue in this manner, adding the remaining test cases one at a time, checking and correcting code as necessary.

- 58| Game 01: The remaining test cases (Full source at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game1.groovy)

// methods, initialization and test case as shown previously // ... // Test Case: Remove an item println 'Test Case: Remove an item' removeItem(game, 'knife') displayItems(game) // Test Case: player picks up an item println 'Test Case: player picks up an item' pickUpItem(game, 'apple', 'Chris') displayItems(game) // Test Case: player drops an item println 'Test Case: player drops an item' dropItem(game, 'apple', 'Chris') displayItems(game) // Test Case: Display the number of items being carried by a player println 'Test Case: Display the number of items being carried by a player' println "Number of items being carried by Chris: ${readNumberOfItemsBeingCarried(game, 'Chris')}\n" // Test Case: Display the number of carriers of an item println 'Test Case: Display the number of carriers of an item' println "Number of players carrying a sword: ${readNumberOfPlayersHoldingItem(game, 'sword')}\n"

The remaining outputs are:

Test Case: Remove an item The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[]] Test Case: player picks up an item The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[Chris]] Test Case: player drops an item The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[]] Test Case: Display the number of items being carried by a player Number of items being carried by Chris: 2 Test Case: Display the number of carriers of an item Number of players carrying a sword: 2

At this point, we consider the first iteration to be complete. A full listing of the script is available on the course web site.

Iteration II: Implementation of a Text-based User Interface

Having demonstrated that the game application executes as expected, we now turn our attention to how a user might interact with it. Clearly there are many possibilities. however, for now, we choose the simplest: a text-based command line interface. Later, we will consider a web-based interface.

For this iteration, we are required to present the user with a text-based menu of options available. Having selected an option, it is actioned and the menu is presented again so that another option can be selected and actioned. This continues until the user selects the Quit option.

We can use the Groovy flow of control constructs, discussed in Lecture 5, to good effect. For example, we have a while loop to control the repeated presentation of the menu, and a switch statement1) to select and action an option.

We can also introduce new methods as necessary. For example, we must elicit an item name, a player name and an option number from the user. These requirements are coded as readItemName, readPlayerName, and readMenuSelection, respectively. The partial listing of Game 02 illustrates the idea. A full listing is available on the course web site.

- Game 02: Text-based user interface (Full source code at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game2.groovy)

import console.* // methods as shown previously // ... def readItemName() { print('\tEnter item name: ') return Console.readLine() } def readPlayerName() { print('\tEnter player name: ') return Console.readLine() } def readMenuSelection() { println() println('0: Quit') println('1: Add new item') println('2: Remove item') println('3: Pick up item') println('4: Drop item') println('5: Display items') println('6: Display number of items being carried by a player') println('7: Display number of players carrying an item') print('\tEnter choice: ') return Console.readInteger() } // initialize the items in a game def game = [ 'bread' : ['Chris', 'John'], 'fork' : ['Chris'], 'sword' : ['John', 'Sally'], 'magic amulet' : ['Sally'], 'apple' : [] ] def choice = readMenuSelection() while (choice != 0) { switch (choice) { case 1: addItem(game, readItemName()) break case 2: removeItem(game, readItemName()) break case 3: pickUpItem(game, readItemName(), readPlayerName()) break case 4: dropItem(game, readItemName(), readPlayerName()) break case 5: displayItems(game) break case 6: def player = readPlayerName() def count = readNumberOfItemsBeingCarried(game, player) println "\n${player} is carrying ${count} items\n" break case 7: def item = readItemName() def count = readNumberOfPlayersHoldingItem(game, item) println "\n${item} is being carried by ${count} players\n" break default: println('\nUnknown selection\n') } // next selection choice = readMenuSelection() } println '\nGame closing'

Notice that the game initialization and supporting methods are unchanged from the previous iteration. However, we have no need for the test code. To test Game 02, we might select each menu item and then display the contents of the game to check the result. A typical interaction, with user interaction shown in bold italic font is:

<html> <pre> e:\dev\at-m42-2009\Case-Studies\case-study-02><b><i>groovy game2.groovy</i></b>

0: Quit 1: Add new item 2: Remove item 3: Pick up item 4: Drop item 5: Display items 6: Display number of items being carried by a player 7: Display number of players carrying an item

Enter choice: <b><i>3</i></b>

Enter item name: <b><i>apple</i></b>

Enter player name: <b><i>Chris</i></b>

0: Quit 1: Add new item 2: Remove item 3: Pick up item 4: Drop item 5: Display items 6: Display number of items being carried by a player 7: Display number of players carrying an item

Enter choice: <b><i>5</i></b>

The game contains: [bread:[Chris, John], fork:[Chris], sword:[John, Sally], magic amulet:[Sally], apple:[Chris]]

0: Quit 1: Add new item 2: Remove item 3: Pick up item 4: Drop item 5: Display items 6: Display number of items being carried by a player 7: Display number of players carrying an item

Enter choice: <b><i>0</i></b>

Game closing </pre> </html>

Iteration III: Implementation With Closures

There are no new functional requirements for this iteration. Our aim is to recode the second iteration so that it is easier to understand and maintain. One potential problem with Game 02 is that the code, which controls the execution, that is the switch statement, will become more an more difficult to understand as more and more options are added.

The closure, discussed in Lecture 6, is a particularly powerful feature of the Groovy language. it represents a block of executable code that is also an Object. Since it is an object, it can be the value in a Map. If its key is a user choice, then we can locate and execute the associated closure without the need for complex control code.

For example, we might have a parameter-less closure, doAddItem, to execute the method addItem from Iteration 2.

def doAddItem = { addItem(game, readItemName()) }

If we have a similar closure for each possible action, then we can have a Map with each user choice as its key and the corresponding closure (actions) as its value.

def menu = [ 1: doAddItem, 2: doRemoveItem, 3: doPickupItem, 4: doDropItem, 5: doDisplayItems, 6: doDisplayNumberOfItemsBeingCarriedByPlayer, 7: doDisplayNumberOfPlayersCarryingItem, ]

Such a structure is often called a lookup table or dispatch table. It is very useful because we can replace complex control code with a table lookup as in:

def choice = readMenuSelection() while (choice != 0) { menu[choice].call() choice = readMenuSelection() }

The partial listing of Game 03 combines these ideas. As with the previous examples complete listings are available on the course website.

- 03: Implementation with closures (full source at at-m42/Case-Studies/case-study-02/game3.groovy)

// methods and initialization as shown previously // ... def doAddItem = { addItem(game, readItemName()) } def doRemoveItem = { removeItem(game, readItemName()) } def doPickupItem = { pickUpItem(game, readItemName(), readPlayerName()) } def doDropItem = { dropItem(game, readItemName(), readPlayerName()) } def doDisplayItems = { displayItems(game) } def doDisplayNumberOfItemsBeingCarriedByPlayer = { def player = readPlayerName() def count = readNumberOfItemsBeingCarried(game, player) println "\n${player} is carrying ${count} items\n" } def doDisplayNumberOfPlayersCarryingItem = { def item = readItemName() def count = readNumberOfPlayersHoldingItem(game, item) println "\n${item} is being carried by ${count} players\n" } def menu = [ 1: doAddItem, 2: doRemoveItem, 3: doPickupItem, 4: doDropItem, 5: doDisplayItems, 6: doDisplayNumberOfItemsBeingCarriedByPlayer, 7: doDisplayNumberOfPlayersCarryingItem, ] def readMenuSelection() { println() println('0: Quit') println('1: Add new item') println('2: Remove item') println('3: Pick up item') println('4: Drop item') println('5: Display items') println('6: Display number of items being carried by a player') println('7: Display number of players carrying an item') print('\tEnter choice: ') return Console.readInteger() } def choice = readMenuSelection() while (choice != 0) { menu[choice].call() choice = readMenuSelection() } println '\nGame closing'

As expected, the execution is the same as Game 02. However, by recoding with closures, we have made it much easier to add extra functionality. For example, we may be required to add an option to display an alphabetic list of the players carrying a particular item. all we have to do is to develop a closure that calls a suitable method:

// method def getPlayers(game, itemName) { return game[itemName] } // closure def doDisplayCarriersOfItem = { def playerNames = getPlayers(game, readItemName()) println "\nPlayers: ${playerNames.sort()}\n" }

The closure is then added to the Map with a suitable key:

menu[8] = doDisplayCarriersOfItem

and the method readMenuSelection updated:

def readMenuSelection() { // as shown previously // ... println('8: Display carriers of an item') // ... }

The important point to realize is that the rest of the code is unchanged. In particular, there is no need to make code that was already complex even more complex. At this point we consider this third iteration, and this case study, complete. </code>

Exercises

- The section String Literals in Lecture 2 discussed the Groovy multi-line text string. recode the method

readMenuSelectionfrom Game 03 to make use of it. What are its advantages and disadvantages? - Implement the option, described above, to display an alphabetic list of the players carrying a particular item.

- Implement a new option to display an alphabetic list of the items in the game.

- Recast Game 03 so that, instead of calling a method, each closure calls a nested closure instead (see Other Closure Features from Lecture 6). What are the advantages of this approach?

—-

Home | Lectures | Previous Case Study | Case Studies | Next Case Study