Table of Contents

~~SLIDESHOW~~

Enterprise Integration Tier Services

In principle, the business logic of an enterprise application could be performed by domain objects which implement a model of the business concept as Plain-Old Java Objects (POJOs).

In practice, the requirements of enterprise applications, namely

- Resource management

- Security

- Data integrity

make the implementation of objects in the business tier much more of a challenge.

Lecture Content

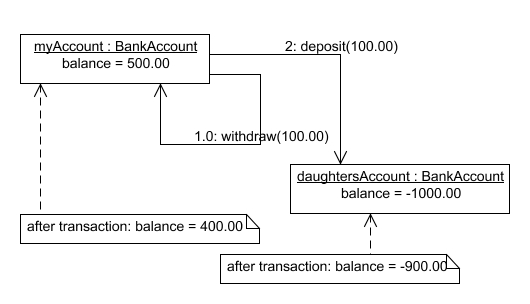

An Example

- Take a simple bank account implemented in Groovy:

class BankAccount { def deposit(amount) { balance += amount } def withdraw(amount) { balance -= amount } // ----- properties ----------------- def number def balance }

This model does not take into account practicalities such as overdraft limits!

Use Case: Make a Transfer

So what's complex about that?

- In principle, this is a very simple business transaction, performed by my bank my behalf.

- In Groovy it would be a two liner…

myAccount.withdraw(100.00) daughtersAccount.deposit(100.00);

- … but what is really happening here?

A Real Bank Transfer (1)

- I have to log in (authenticate myself) to my bank.

- I must be authorized to access my bank account and to make a transfer.

- My daughter’s account has to be set up as an account that I can transfer funds to.

- I must have sufficient funds.

…

A Real Bank Transfer (2)

- After the money is transferred there must be £400.00 in my account and -£900.00 in my daughter’s.

- If something goes wrong, I should have £500.00 in my account and my daughter’s overdraft will not have improved.

- My daughter and I do not have a bank account at the same bank.

…

A Real Bank Transfer (3)

- Both banks have to keep a record of this transaction.

- I would expect to see the transaction in my next statement (or immediately that funds have cleared if on-line), and so would my daughter.

Comments

- On the previous slide, only the highlighted term is actually an application issue addressed in the business logic.

- All the rest have to addressed by the business tier at the two banks concerned.

- The issues illustrated are typical of those found in the business tier:

- Transactions must be secure

- Transaction is distributed

- Data integrity must be assured

- There must be an audit trail

Notes

Transactions must be secure: I must provide proof of identity (authentication) and be authorized to make the transfer. My bank must authenticate itself and be authorized to make a funds transfer to my daughter’s account.

Transaction is distributed. Accounts are maintained in different machines. I access my bank across the internet, the banks access each other across the internet.

Data integrity must be assured: money can only be in my account or in my daughter’s. It cannot be lost in transit. If a failure occurs, both accounts should roll-back to their original state. The object representing my account may not even be on the same server the next time I log in: but the balance has to be correct!

There must be an audit trail for legislative and customer information purposes.

Lecture Content

The Key Business Tier Services

Having seen this simple example, we can straight away identify some key services provided to objects in the Business Tier:

- Transaction support

- Persistence

- Security

- Transparent resource location

- Logging

Transaction Support

The atomic withdraw and deposit methods and the entities representing the two bank accounts have to be protected inside the transfer transaction.

- When I start to transfer funds, my account is locked until the funds have been received.

- When funds have been received, my balance will be reduced.

- Similarly my daughter’s account is also protected.

- Only if the transaction succeeds is it committed and the database records for the accounts will be updated.

- If anything goes wrong, the whole transaction is rolled back (or undone).

Persistence

- The main purpose of persistence is to allow data to survive runs of the application.

- To survive a crash.

- To rollback to a known state after a failed transaction.

- Or simply to be stored in non-volatile memory.

- Your business objects want this to just happen!

- Transparent persistence, as discussed in the last lecture, is obviously important,

- but persistence should also be a key part of transaction management and is a cornerstone of data integrity.

Security

- Business applications have to be secure.

- Agents have to authenticate themselves to the business tier so that they can be identified.

- Methods can only be called by agents authorized to call them.

- Agents may have different authorization: consider the authority a customer, payee, bank teller, bank manager or unauthorized third party may have to your account.

- Wider issues: security of communications, security of the business tier from unauthorized access, etc.

Transparent resource location

- In systems like on-line banking there are many possible gateways to the bank account information:

- Bank’s own systems, Other banks, Traders making electronic funds transfers, ATMs, Internet banking, Mobile phones, Digital TVs etc.

- Whatever system is used, a single database record represents my bank account.

- As server load on my bank’s system increases, extra machines are brought into use.

- All three tiers of the enterprise application may be replicated

- Wherever it is located, my bank account’s state should be consistent.

Logging

- Logging is required so that a record of each transaction is kept somewhere.

- Obvious use in managing an application server, but also necessary for other purposes. For example:

- Telcos, banks and ISPs are legally required to keep records of certain transactions.

- Customers need access to activity records (statements)

- Service providers need records for billing purposes

- Disputes will need to be resolved by consulting records.

- Logging can be as simple as a text file or may itself be supported by a persistent store.

Lecture Content

Business Tiers are Complex

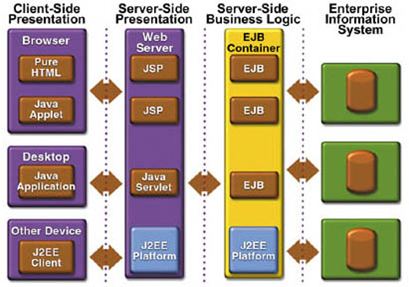

What's Java's Solution?

- The Java 2 Enterprise Edition defines many APIs that can be used to build enterprise applications.

- We discussed some of these in the lecture on Distributed Application Architecture.

- For the particular requirements of the Business Tier, J2EE defines an architecture specified around Enterprise Java Beans (EJBs) and the EJB container.

- EJBs are the components which represent the business entities and business processes.

- The EJB container provides the business tier services.

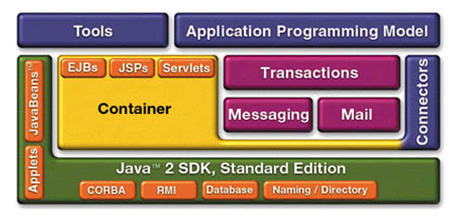

The Application Programming Model

Components, Containers and Connectors

- Three fundamental parts of an enterprise application.

- Components are the key focus of application developers,

- System vendors implement containers and connectors to conceal complexity and promote portability.

Java EE Architecture

EJB Components

- Elements of reusable business logic that adhere to the strict standards and design patterns defined in the EJB specification.

- Allows components to be portable.

- Allows other services:

- Security, caching and distributed transactions to be performed on behalf of the components.

- Development is the responsibility of an EJB provider (that is a programmer).

EJB Container

- EJB Container and Server: the run-time environment provided by the EJB Container/Server Provider.

- Provides the services that the EJB needs such as:

- Java Naming and Directory Interface (JNDI): for lookup across networks

- Java Transaction API/Java Transaction Service (JTA/JTS): for controlling transactions

- CORBA and RMI/IIOP: for communication between components and with container

- JDBC and Java Persistance Architecture (EJB 3) for persistence of data

- Servlets, JSP and Java Server Faces (JSF) for interaction with client (interface services)

- Security for access control and ensuring secure transactions

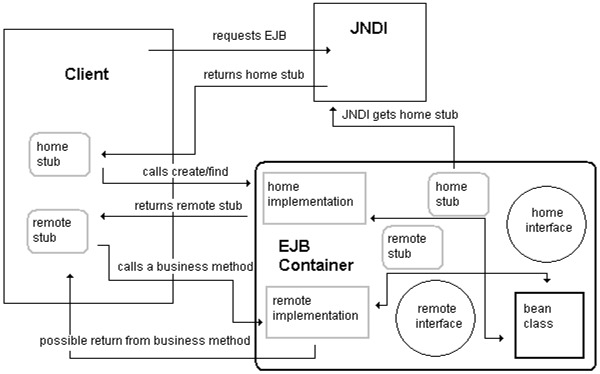

Anatomy of an EJB

An EJB consists of a number of pieces, including the bean itself, some interfaces, and an information file. Everything is packaged into a special jar file.

- Enterprise Bean

- Home Interface

- Remote Interface/Local Interface

- Deployment Descriptor

- EJB-Jar File

Notes

- Enterprise Bean: implements EJB interface, provides business logic.

- Home Interface: used as a factory for an EJB. Clients use home interface to find an instance of a bean or to create a new instance.

- Remote Interface/Local Interface: interfaces to your EJB that can be used by remote objects (using RMI) or local objects (in the same JVM).

- Deployment Descriptor: an XML file that describes the EJB. Can be used by the deployer to configure the EJB for a container.

- EJB-Jar File: packages Bean, Home, Remote, Local interfaces and deployment descriptor.

Originally EJB relied heavily on interfaces and XML deployment descriptors. With the introduction of annotations to Java in Java SE 5, this has gradually changed.

EJB Operation

- EJB Container implements the Home and Remote interfaces

- Container thus responsible for managing the lifecycle of the bean (through home interface) and for managing requests from clients via the remote interface, e.g. by sharing requests via threads or pooling.

- All requests are “proxied” through the EJB container which can then control transactions, security and caching behind the scenes.

Types of EJBs

- Session Beans are used to represent use-cases or work flow on behalf of a client. They represent operations on the persistent data but not the data itself. Two types:

- Stateless session beans

- Simplest type of EJB component.

- No record of history with client so can be reused on the server side

- State has to be stored outside of the EJB.

- Statefull session beans

- Maintain state between invocations

- Pooled and cached by container

Entity Beans

- Represent persistent data and its behaviour.

- Can be shared among clients.

- Managed saving and restoring of data by container ensures that data “lives on” between container invocations.

- Container managed persistence hands responsibility of maintaining the data to the container. Usually via a database. Persistence just happens!

- Bean managed persistence makes the bean provider responsible for persistence.

Why So Complex?

- Container provides the Business Tier services to the beans.

- Any access to a business object has to be intercepted so that it can be authorized, controlled within a transaction, transparently persisted, and logged.

- This service is provided by the container via hooks in the remote or local interface and passed on to the bean itself only if allowed.

- The model assumes that client access will be remote via RMI, so we need to identify a “constructor” for the component via the home interface.

How it works

Lecture Content

Developing an EJB

- The remote interface must be public.

- The remote interface must extend the interface javax.ejb.EJBObject.

- Each method in the remote interface must declare java.rmi.RemoteException in its throws clause in addition to any application-specific exceptions.

- Any object passed as an argument or return value (either directly or embedded within a local object) must be a valid RMI-IIOP data type (this includes other EJB objects).

Remote interface for the DateHere EJB (EJB 2 version)

- 1| Example 1: Remote interface for the DateHereBean (EJB 2)

import java.rmi.*; import javax.ejb.*; package uk.ac.swan.atm42.ejb; public interface TimeHere extends EJBObject { public String getTimeHere() throws RemoteException; }

Remote interface for the DateHere EJB (EJB 3 version)

In EJB 3, the details can be left to the container: interface is a plain-old-Java interface annotated with javax.ejb.Remote.

- 1|Example 2: Remote interface for the DateHereBean (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHere.java)

extern> http://cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHere.java

The Home interface

- Factory where the component will be created.

- It can define create methods, to create instances of EJBs

- finder methods, which locate existing EJBs and are used for Entity Beans only.

The Home Interface Specification

- The Home interface must be public.

- The Home interface must extend the interface

javax.ejb.EJBHome. - Each create method in the Home interface must declare

java.rmi.RemoteExceptionin itsthrowsclause as well as ajavax.ejb.CreateException. - The return value of a create method must be a Remote Interface.

- The return value of a finder method (Entity Beans only) must be a Remote Interface or java.util.Enumeration or java.util.Collection.

- Any object passed as an argument (either directly or embedded within a local object) must be a valid RMI-IIOP data type (this includes other EJB objects)

- In EJB 3 the Home interface is provided automatically by the container and you don't need to provide code.

Home interface for the TimeHere (EJB 2)

- 1|Example 3: Remote interface for the DateHereBean (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereHome.java)

extern> http://cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereHome.java

Business Logic

You can now implement the business logic. When you create your EJB implementation class, you must follow these guidelines:

- The class must be

public. - The class must implement an EJB interface (either

javax.ejb.SessionBeanorjavax.ejb.EntityBean). - The class should define methods that map directly to the methods in the Remote interface. Note that the class does not implement the Remote interface; it mirrors the methods in the Remote interface but does not throw

java.rmi.RemoteException. - Define one or moreejbCreate()methods to initialize your EJB. - The return value and arguments of all methods must be valid RMI-IIOP data types.

TimeHereBean (Session Bean) EJB 2 Version

- 1| Example 4: SessionBean implemented using EJB 2 conventions

// Simple Stateless Session Bean // that returns current system time. package uk.ac.swan.atm42.ejb; import java.rmi.*; import javax.ejb.*; public class TimeHereBean implements SessionBean { private SessionContext sessionContext; //return time here public String getTimeHere() { return new Date().toString(); } // EJB methods public void ejbCreate() throws CreateException {} public void ejbRemove() {} public void ejbActivate() {} public void ejbPassivate() {} public void setSessionContext(SessionContext ctx) { sessionContext = ctx; } }

Version 3 EJBs

- Most of the code in previous example is “boiler plate” providiing “hooks” for the container.

- EJB uses Java 5 annotations to enable the container to provide its own hooks.

- EJB is now a “Plain Old Java Object” (POJO)) annotated with

javax.ejb.Stateless

TimeHereBean (Session Bean) EJB 3 Version

- 1| Example 5: SessionBean implemented using EJB 3 conventions (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereBean.java)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereBean.java

Deployment Descriptor (EJB 2)

An XML file that describes the EJB component. Should be stored in a file called ejb-jar.xml.

- 1|Example 6: Deployment Descriptor for the TimeHereBean (not required in EJB 3 containers) (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/ejb-jar.xml)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/ejb-jar.xml

Deploying the EJB

- The files must be archived inside a standard Java Archive (JAR) file. The deployment descriptors (if used) should be placed inside the

/META-INFsub-directory of the Jar file. - Once the EJB component is defined in the deployment descriptor, the deployer should then deploy the EJB component into the EJB Container.

- The deployment process is quite “GUI intensive2 and specific to the individual EJB Container.

- The deployment process creates some client stubs for calling the EJB component. These classes should be placed on the CLASSPATH of the client application.

- When a client program wishes to invoke an EJB it must look up the EJB component inside JNDI and obtain a reference to the home interface of the EJB component. The Home interface is used to create an instance of the EJB.

The Client

- Here a simple Java program but could just as easily be a servlet, a JSP or even a CORBA or RMI distributed object.

- 1|Example 7: Client program for TimeHereBean (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereClient.java)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereClient.java

- 1| Example 7: Client program for TimeHereBean (at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereClient.java)

extern> http://www.cpjobling.org.uk/~eechris/at-m42/Examples/lecture15/TimeHereClient.java

Lecture Content

Is the Java Solution a Good Solution?

- During 2004, the developer community decided that the answer is probably no.

- EJB 3 was a response to this, and uses annotations to simplify it.

- We will discuss this issue, and some of the alternatives in the final lecture.

- The TimeHere session EJB example gives a flavour of the complexity! To run the example, you’ll need an implementation of a Java EE container (e.g. Glassfish) to which you can deploy the bean.